Notebook photo by Mike Tinnion on Unsplash.

Common user flows

Some applications are like Swiss Army Knives. They provide many different individual tools, and it is up to each user to find the right one for their job and use it effectively. Other software is highly optimized for clear use cases and provides specific, more linear workflows for each one. And many applications use both approaches at different times. Particularly for new users and initial software setup, offering linear workflows (also known as wizards) can help complete tasks.

Let’s take a look at some common user needs and workflows that can be created for them.

Orientation #

This step is often overlooked, but before anyone uses your product, they first need to find out it exists, understand and develop interest and decide to start using it. If users cannot quickly learn the application’s purpose and benefits, they are less likely to use it. Also see the first three phases of the usage life cycle.

Software download & installation #

Mobile app stores do a good job of providing previews of what using an app will be like. Through copy, videos, images, and reviews, users can make informed decisions about the product they are evaluating. Open-source software is typically downloaded via a website or from Github, and each project decides what information to present.

Here are two different examples of webpages for downloading bitcoin wallet software. Which one allows users to better understand what using the software will be like? Which one builds more trust?

BlueWallet landing page on the App Store

The App Store landing page includes screenshots, a description, user reviews, updates to the latest version, and information about the developer. The bitcoincore.org landing page does not allow me to get an idea of how the product works, what it looks like, or what others think of it. Instead, it provides multiple download links, requirements, and information about how to verify that it is indeed the software I am looking for. The two approaches are for different phases of the usage life cycle. One is for the aware user who wants to determine whether they are interested in the product. The other is for interested users who want to start using the product. Make sure to satisfy both of these users.

Software onboarding #

Bitcoin is complex, and so it is recommended to think through and carefully shape the first experience users have in your product. Without being overwhelming or getting into too much detail, this user flow should explain core concepts and features that allow users to create mental models on how they will use the application.

Onboarding may be purely informational based on the content, but it also includes an initial setup that helps personalize the software towards the users’ specific needs and context. After onboarding, users are mostly on their own, so the goal is to leave users with a clear idea of achieving what they came for.

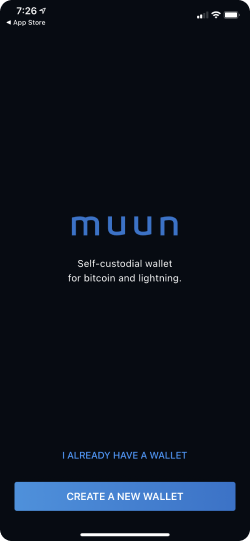

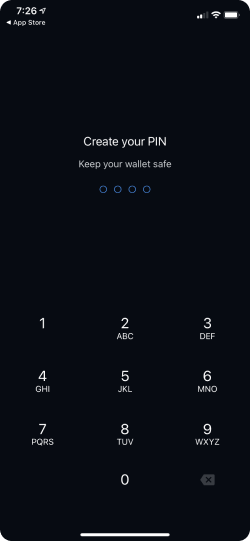

The example screens below from the Muun iOS wallet (taken January 2021) use several different methods:

- Guide the user through information and setup one step at a time

- Offer carousels of information users can choose to read (or skip)

- Provide simple prompts of key actions

- Confirm users are aware of their responsibilities

You can find more screenshots here.

Cover screen for new users.

Choosing a PIN for security.

Letting users know that a wallet was successfully created.

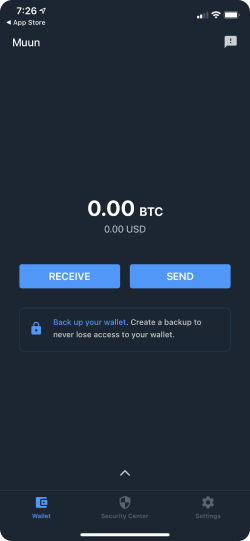

The home screen with a prompt to back up the wallet.

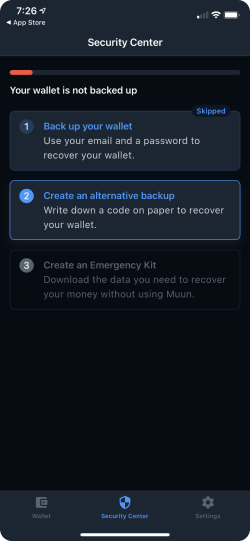

The security center guides users through different backup options.

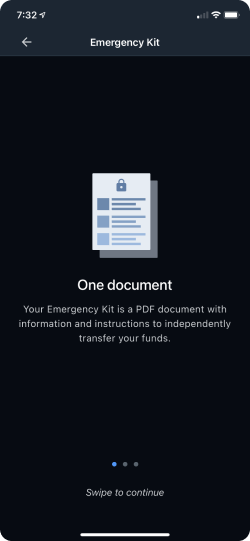

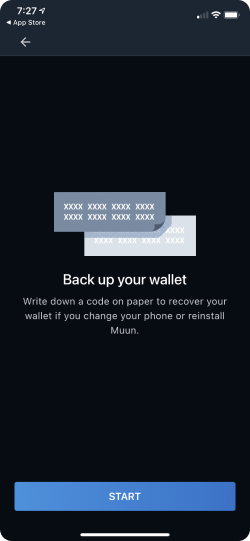

An instructional screen to inform users about the security option they are about to set up.

Another informational screen for the manual backup option.

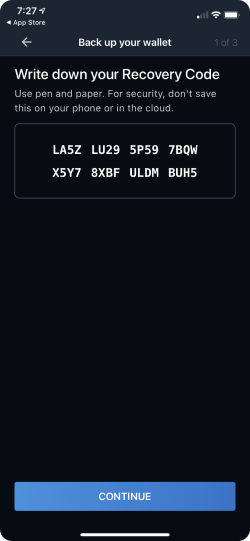

A screen that requests users to copy their recovery code.

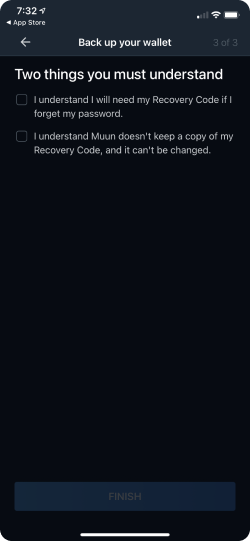

Confirming that users understand their responsibility in the security mechanisms of the app.

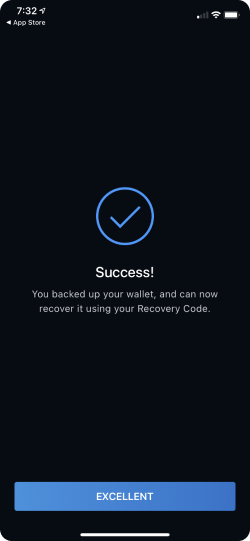

Giving users confirmation that the app is set up properly.

See the first use to learn more on this topic.

Creating a new wallet #

By wallet, we normally mean the wallet application. In this context, we will instead talk about creating the bitcoin wallet (the data structure which stores and manages the user’s private key(s), which the software interacts with to control funds on the bitcoin blockchain.

A good starting point today is an HD wallet implemented according to BIP 32, 39, 43, 44, 49, 84 and 380.

Some older software may create wallets with outdated technical formats, while others allow users to choose specific formats for their particular needs. Generally, this is difficult to understand for regular users and should either be automatically handled with good default settings, or explained in layman’s terms. Wallets Recovery provides a great overview of different implementations and how nuanced some of the differences are.

Most modern wallet applications should aim to support the lightning network in addition to the base layer. While there are different options for how the applications interact with a lightning network node, an HD wallet works fine for storing the required keys.

Wallets can also be created with control shared between several other wallets, so called multi-key wallets (or multi-signature / multi-sig). This is typically done to increase security.

Securing a wallet #

Like fiat currencies, securely storing funds can be as simple as storing some coins in your pocket or highly complex with multiple banks’ safety deposit boxes. For self-custodial wallets, all of this is in the users’ hands, although wallet software ideally provides guidelines and support to more easily follow best practices. See also, the Private key management section and Protecting a wallet.

Backing up a wallet #

To enable recovery of a wallet that uses the manual backup scheme for private key management, we should ask users to securely back up their keys with their recovery phrase (and for full compatibility, derivation path and output descriptors) when they create new wallets. See also, Wallet interoperability and bitcoin backups.

Importing an existing wallet #

If the user is in possession of the recovery phrase for a bitcoin wallet, they should be able to import it into any application that supports the same standards. Some technical caveats apply, generally users are best advised to attempt recovery of a wallet with the same application as the wallet was created with for full compatibility. See also, Wallet interoperability and Restoring a wallet.

Sending bitcoin #

While we all prefer to receive bitcoin, there are times when we need to send them to others. At the core, sending bitcoin can be a very simple matter of entering an address, amount, and tapping “Send”. It can also scale up to a much more complex interaction when batching transactions or using a multi-signature wallet.

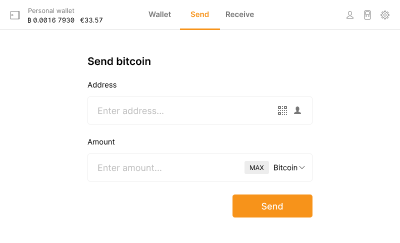

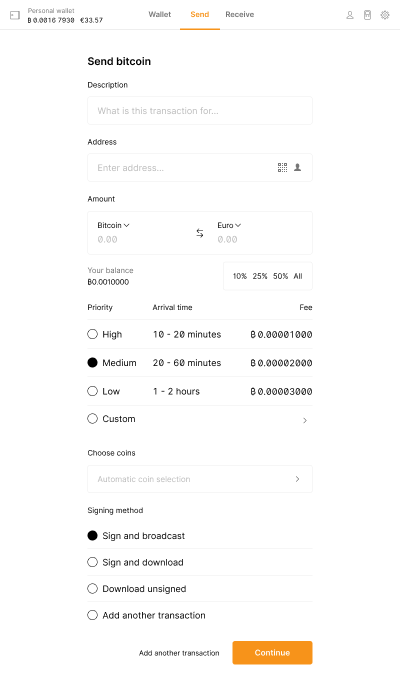

A UI for sending bitcoin with just the basic information (source).

An overly complex interface with advanced send options (source).

Bitcoin can be sent two ways; on the primary base layer, or the secondary lightning network layer.

On the base layer, once a transaction is broadcast from a wallet, the bitcoin network starts processing it. Users may want to stay informed about this progress, particularly when a transaction takes longer than expected. The average transaction time on the base layer is 10 minutes, but this can vary a lot depending on the fee the sender was willing to pay. In extreme cases, it is possible to retroactively increase the transaction fee to get validated faster with a Replace-by-Fee technique.

On the lightning network, transactions happen inside payment channels that are established on the base layer between two participants. The state of ownership of the bitcoin within the channel is maintained by the participant lightning network nodes. Transactions on this layer are almost instant, and have negligible fees. However, there are fees to open and close channels, as this is recorded on the base layer.

To find out more, visit the Sending bitcoin page.

Requesting bitcoin #

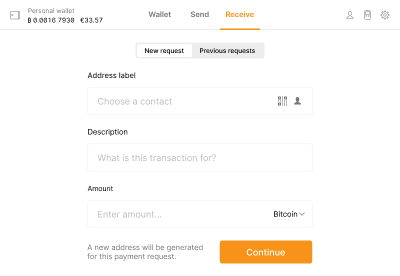

Equivalent to creating an invoice, requesting bitcoin involves entering information about this specific transaction and sharing it with the payer.

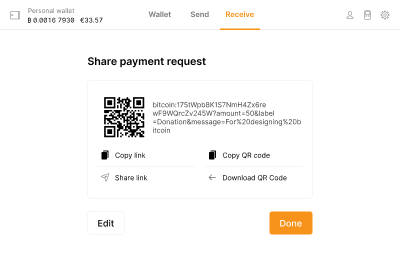

A payment request starts with entering invoice information.

Then the payment request needs to be shared with the payer.

For the simplest form of base layer requests, the receiver only needs to share one of their addresses with the sender, who can themselves input the amount.

While it is possible to re-use the same receiving address repeatedly, this practice is highly discouraged for privacy reasons.

For more information-rich base layer requests, BIP 21 describes a URI scheme to turn requests into links that can be shared like any other link. On click, wallets that support this scheme can immediately show the send screen with the correct information pre-filled. Links can also be encoded and transmitted via QR code. Since the scheme also allows for the inclusion of an address label and transaction description, it allows both sender and recipient to stay organized.

For requests on the lightning network, the receiver needs to create a lightning invoice that includes the amount, and then share the invoice with the sender.

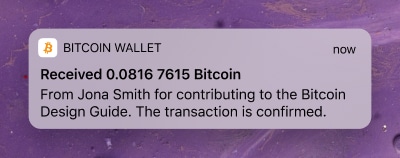

Receiving bitcoin #

Once a user has requested payment, they are naturally interested in knowing when sent and confirmed. Even when the request was not specifically made, it is nice to know when you receive money. This can ideally be communicated via push notifications or similar mechanisms. Since the bitcoin network does not have native functionality to push updates to wallet clients, this requires wallet software to regularly check for new transactions or the use of a trusted third-party service.

A user may also want to check in and see if any previous requests have not been completed yet. This is easily possible if the user has initiated all requests on the same wallet and used a new address for each one. In this case, a request can be considered fulfilled if at least one payment has been received with the total amount the user asked for. It is not as clear if addresses are getting re-used (how to tell which payment was for which purpose?) or the request has been made with another wallet (as this metadata is not stored and synced via the bitcoin network).

On the lightning network, receiving bitcoin requires an invoice. This makes it easy to track if payments have been completed or not.

Managing transactions #

While the bitcoin network only stores transactions, a wallet is more than just a list of bitcoin sent and received. Behind each transaction is an interaction between people and companies (or software). To make sense and work with transactions, they typically need to apply an organizational system. This could be a list of contacts they assign addresses to, tags like “allowance” or “business expenses,” or simply describing what a transaction was for.

Wallet software can support users and make this easier by offering organizational features and automated organization as it is possible.

This is not only helpful to users but can also help improve privacy. Since the individual transaction history can be traced, it is helpful to isolate transactions by the sender and/or recipient. If I receive bitcoin from an exchange and then pay a store, then there is a chance that personal information about myself can be uncovered by making that connection. With well-labeled transactions, wallets can help users avoid this type of situation. For more, see the Activity page.

Switching wallets #

There are several reasons a user might want to switch wallets.

A different wallet application might have features they need, or be better supported than the one they originally created the bitcoin wallet with. Importing the wallet with the recovery phrase into the new application should be possible, and will be free from fees as no transfer of funds is happening.

The owner may want to increase the security of their wallet, either by using a single-key wallet with a passphrase, or a multi-key wallet. As both of these include transferring funds to a new bitcoin wallet, there will be fees to pay.

In the worst-case scenario, the wallet might have been compromised, and funds should be saved by sending them all to a different bitcoin wallet.

Whatever the reason, the import and backup of wallets is a vital function for users that applications should support. While it is easy to send all funds to a new address, additional meta and state data stored in wallet applications also need to be considered for full compatibility. It’s not recommended to switch wallets that include funds on the lightning network, as standards for backing up channel state have yet to emerge. See also, Wallet interoperability.

Wallet maintenance #

It is not necessarily intuitive that a wallet may need maintenance, but there are a few actions users should regularly do in order to ensure their money is secure and private.

Sweep dust #

This is similar to exchanging many small coins into bills (like exchanging 100 one-dollar bills to a single one-hundred dollar bill). Dust refers to small amounts of unspent bitcoin in a wallet. If they add up, future transaction fees can become costly. That’s because fees are partially based on transaction size. This size increases with every output from a previous transaction that is included. Sweeping dust helps by making a transaction to yourself that turns the many outputs with small amounts into a single output with a larger amount. This is typically done when few transactions are being done on the bitcoin network, which is another factor in fee calculation (senders choose how much they want to pay in fees, and the network prioritizes transactions that pay more).

Mixing coins #

Mixing coins is a technique to improve transaction privacy by making a special transaction. Multiple senders participate in the same transaction by sending and receiving identical amounts of bitcoin. Because this intertwines the transaction history of those coins, it becomes much harder to trace the individual coins and their respective owners.

Test hardware wallets #

Whether it’s to ensure a hardware wallet still works, or to install a software update, it is recommended to verify that everything still operates as expected regularly. If a hardware wallet is exclusively used with a particular application, then the application can offer users support with this task (for example, by reminding users to check the hardware wallet every six months). The higher the amount stored, the more important it is to regularly check the setup’s health.

Resolving a problem #

This can be a tricky experience to address. For one, non-custodial cryptocurrency management by nature places a lot of responsibility on the user. This also puts much of the burden of solving problems on users. The second aspect is that open-source software typically relies on online documentation and forums for “customer service.” Ideally, the software helps prevent errors as much as possible through validating user input and requiring extra approvals for impactful actions. When this is not possible, though, and errors do occur, they should be communicated as clearly as possible.

Our next section introduces a framework with a focus on the usage life cycle.